Senin, 08 Desember 2008

Lombok adalah potret sebuah mozaik. Ada banyak warna budaya dan nilai menyeruak di masyarakatnya. Mozaik ini terjadi antara lain karena lombok masa lalu adalah merupakan objek perebutan dominasi berbagai budaya dan nilai. Antara sasak (suku dominan di Lombok) yang pribumi yang harus berhadapan pula dengan pengaruhnya Hindu Bali yang dominan di Lombok Barat dan pengaruh Islam Jawa yang kuat ekspansinya di Lombok Tengah dan Lombok Timur.[1]

Dari segi geografis, Lombok juga mozaik dari berbagai kondisi. Lombok Barat (sekarang terbagi menjadi Kab. Lombok Barat dan Kotamadya Mataram) adalah daerah yang dikenal paling subur. Karenanya, di masa lalu Lombok Barat menjadi salah satu sasaran Bali (tepatnya Kerajaan Karang Asem) dalam mengembangkan pengaruhnya. Tak aneh, kalau di daerah ini Pura-Pura tempat sakral bagi persembahyangan kaum Hindu masih banyak dijumpai. Orang Hindu dari Ampenan, Mataram dan Cakranegara datang ke Lombok Barat untuk melakukan ritual keagamaan.

Dua kawasan lainnya, yakni Lombok Tengah dan Lombok Timur juga diwarnai kondisi yang berbeada. Lombok Tengah adalah daerah miskin tanahnya kurang subur. Sedangkan Lombok Timur terhitung sedikit lebih subur jika dibanding Lombpok Tengah karena kawasannya yang terletak di dataran tinggi Gunung Rinjani (Gunung tergolong Merapi aktif di Lombok). Dua kawasan inilah yang di masa lalu menjadi benteng Islamisasi kerajaan Islam Jawa di kawasan timur nusantara. [2]

Pengaruh Kerajaan inilah yang kemungkinan menyebabkan Islam menjadi agama mayoritas suku asli Lombok sekarang ini. Tetapi klaim ini masih perlu diuji kembali, karena masuknya Islam di Lombok belum di ketahui secara pasti. Akan tetapi diperkirakan pada abad ke-16 yang di bawa oleh Sunan Prapen, Putera dari Sunan Giri, salah seorang Wali Songo di Jawa.

Dalam perkembangan selanjutnya, Islam merupakan dan menjadi sebuah faktor utama dalam masyarakat Lombok. Hampir 95 % dari penduduk kepulauan itu adalah orang Sasak dan hampir semuanya adalah muslim. Seorang etnografis bahkan jauh mengatakan bahwa “menjadi Sasak berarti menjadi muslim”. Meskipun pernyataan ini tidak seluruhnya benar (karena pernyataan ini mengabaikan popularitas Sasak Boda),[3] sentimen-sentimen itu dipegangi bersama oleh sebagian besar penduduk Lombok karena identitas Sasak begitu erat terkait dengan identitas mereka sebagai muslim.

Bila lombok dicap sebagai “sebuah pulau dengan 1000 masjid” yang mungkin meremehkan keberadaan sejumlah masjid kecil di Pulau tersebut, pesannya adalah jelas. Lombok sangat terkenal di Indonesia sebagai sebuah tempat di mana Islam diterima secara serius dan tipe Islam yang dipraktekkan adalah pada umumnya adalah agak kaku dan bentuknya ortodoks bila dibandingkan dengan di daerah lain di negeri ini.[4] Islam sebagaimana ia di praktekkan dan di pahami di Lombok menampilkan sejumlah variasi yang signifikan. Dalam tradisi keislaman masyarakat Sasak akan ditemukan dua varian Islam yaitu “Islam Wetu Telu ” dan “Islam Waktu Lima ”.[5]

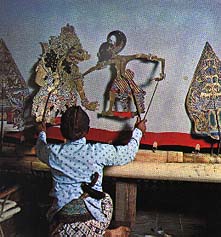

Wetu Telu adalah orang sasak yang, meskipun mengaku sebagai muslim, masih sangat percaya terhadap ketuhanan animistik leluhur (ancestral animistic deitis) maupun benda-benda antropomorfis (anthropomorphised inanimate objects). Dalam hal itu mereka adalah panteis. Sebaliknya, waktu lima adalah orang muslim sasak yang mengikuti ajaran syari’ah secara lebih keras sebagaimana diajarkan oleh al-Qur’an dan Hadis. Mengikuti dikotomi Geertz dalam Religion of Java, agama wetu telu lebih mirip dengan Islam abangan yang sinkretik, walaupun waaktu lima tidaklah seperti bentuk Islam santri.[6]

Yang unik dari praktik keagamaan atau ibadah Wetu Telu adalah adanya perbedaan tata cara ibadah yang berbeda-beda antara daerah satu dengan lainnya. Di Sembalun daerah dingin Leren Gunung Rinjani (Lombok Timur), mereka hanya menjalankan solat Ashar pada

Islam Sasak (Islam Wetu Telu): Wujud Dialektika Islam Dengan Budaya Sasak

Agama sasak atau lebih spesifik lagi Islam sasak merupakan cermin dari pergulatan agama lokal atau tradisional berhadapan dengan agama dunia yang universal dalam hal ini Islam. Seperti yang terjadi di Bayan (Lombok), [7] Islam Wetu Telu (Islam Lokal) yang banyak dipeluk oleh penduduk Sasak asli dianggap sebagai “tata cara keagamaan Islam yang salah (bahkan cenderung syirik)” oleh kalangan Islam Waktu lima, sebuah varian Islam universal yang dibawa oleh orang-orang dari daerah lain di Lombok. Tak pelak, Islam waktu lima sejak awal kehadirannya disengaja untuk melakukan misi atau dakwah Islamiyah terhadap kalangan Wete Telu.

Secara sederhana barangkali dapat dikatakan bahwa Wetu Telu merupakan sejenis Islam yang dijalankan dengan tradisi-tradisi lokal dan adat sasak. Varian Islam ini lebih mirip dengan Islam abangan atau Islam Jawa di Jawa, seperti yang ditulis Mark Woodward dalam buku “Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan”.[8] Dalam agama wetu Telu, yang paling menonjol dan sentral adalah pengetahuan tentang lokal, tentang adat, bukan pengetahuan tentang sebagai rumusan doktrin yang datang dari Arab.Akan tetapi juga bukan tidak menggunakan Islam sama sekali, dalam doa-doa, temapat peribadatan masjid dan beberapa praktek ibadah lain, merupakan introduksi keislaman mereka.

Penyebutan istilah Wetu Telu mempunyai perspektif yang berbeda-beda. Komunitas Waktu Lima menyatakan bahwa Wetu Telu sebagai waktu tiga (tiga:telu) dan mengaitkan makna ini dengan reduksi seluruh ibadah Islam menjadi tiga. Orang Bayan[9] sebagai penganut terbesar Islam Wetu Telu ini, menolak penafsiran semacam itu. Pemangku Adatnya mengatakan bahwa, term wetu sering dikacaukan dengan waktu. Wetu berasal dari kata “metu” yang berarti “muncul” atau “datang dari”. Sedangkan “telu” artinya “tiga”. Secara simbolis makna ini mengungkapkan bahwa semua makhluk hidup muncul melalui tiga macam sistem reproduksi, yaitu melahirkan (disebut menganak), bertelur (disebut menteluk) dan berkembang biak dari benih (disebut juga mentiuk). Term Wetu Telu juga tidak hanya menunjuk kepada tiga macam sistem reproduksi, tetapi juga menunjuk pada kemahakuasaan Tuhan yang memungkinkan makhluk hidup untuk hidup dan mengembangkan diri melalui mekanisme reproduksi tersebut.[10] Sumber lain menyebutkan bahwa ungkapan Wetu Telu berasal dari bahasa Jawa yaitu Metu Saking Telu yakni keluar atau bersumber dari tiga hal: Al-Qur’an, Hadis dan Ijma. Artinya, ajaran-ajaran komunitas penganut Islam Wetu Telu bersumber dari ketiga sumber tersebut.[11]

Komunitas Islam Wetu Telu ini dalam perjalanannya mulai terdesak sedikit demi sedikit oleh arus modernitas, ortodoksisme Islam dan “serangan” dakwah terus menerus yang dilakukan oleh Islam Waktu Lima ( jenis Islam puritan yang ada di Lombok), serta implikasi massif dari kebijakan politik terutama proyek transmigrasi lokal ke kawasan adat mereka.[12] Mengapa selalu termarginalkan nasib keyakinan Islam yang bernuansa lokal? Bukankah ini justru bukti pluralitas keagamaan dalam Islam sendiri, yang menunjukkan keramahannya terhadap budaya lokal.Padahal beralihnya Orang Sasak dari Boda (sinkretisme Hindu-Budha) menjadi Islam, kemudian dari muslim sinkretis dan nominal –disebut Wetu Telu- menjadi Islam yang sempurna –Waktu Lima- memperlihatkan dinamisme kultural dalam cara Islam disebarkan, kemudian diserap, diakomodasi dan diekspresikan di Indonesia. Dinamisme kultural juga melatari fakta bahwa aktifitas penyebaran dan penanaman ajaran Islam merupakan proses panjang dan berkesinambungan dalam antagonisme dan asimilasi tiada henti.

Lepas dari berbagai stigma yang dilekatkan pada Islam lokal (seperti Jawa dan Sasak) ada baiknya menyimak pendapat Eickelman bahwa melihat Islam lokal dengan melepas kaitannya dengan Islam normatif adalah sebuah pandangan yang gagal melihat fakta betapa kebanyakan kaum muslim menjadikan normativitas Islam sebagai esensi untuk memaknai praktik dan keyakinan Islamnya. Dalam konteks ini,adalah menarik melihat penolakan Braten terhadap pandangan Geertz. Braten mengawalinya dengan sebuah penelitian di salah satu desa yang dikenal kuat Islamnya di wilayah Jawa, tepatan di Desa Batasan, kabupaten Semarang. Desa tersebut terkenal yang sangat fanatik Islamnya terutama NU. Berdasarkan spirit harmoni yang membentuk sikap hidup masyarakat Jawa, Braten menemukan bahwa dakwah Islam sama sekali tidak dilakukan dengan melangsungkan oposisi terhadap tradisi lokal. Sekali lagi bahwa ini bukan dengan mengorbankan Islam atau mengorbankan tradisi, tapi mewarnai tradisi dengan spirit Islam. Bacaan Bismillah menjadi pembuka bagi seluruh akatifitas kemasyarakatan. Masyarakat bahkan memiliki caranya sendiri untuk tetap menjaga harmoni itu. Mereka tahu bahwa adat tetap dilakukan dengan tanpa mencederai jiwa Islam. Sementara Islam dilakukan dengan tetap menjaga harmoni tradisi masyarakat. Oleh sebab itu, yang terpenting bahwa tuduhan bahwa praktik-praktik Islam lokal, seperti Jawa dan Sasak, semata-mata bersifat animis-hindu-budhis dan tidak memiliki landasannya secara normatif dalam doktrin Islam, patut dipertanyakan ulang. Apa yang selama ini dianggap sebagai kepercayaan dan praktik Islam lokal nyatanya juga dipraktikkan oleh banyak kaum muslim di belahan dunia lain. Untuk konteks nusantara, ia hadir mengemuka bersama dengan proses panjang islamisasi ini sendiri.[13]

Aspek Lokalitas dalam Fiqh Islam

Salah satu disiplin keilmuan Islam yang menjadi fakta sejarah bagaimana doktrin Islam mengaprisiasi budaya lokal adalah ilmu fiqih. Sebagai institusi pembebas, fiqh harus dimaknai proses bukan produk monumental. Hukum Islam atau fiqh, memiliki karakteristik yang jauh berbeda dengan hukum dalam pengertian ilmu hukum modern. Hukum Islam dikembangkan berdasarkan wahyu di samping pemikiran manusia dan juga diwarnai oleh ciri kelokalan di samping ciri keuniversalan. Dengan demikian, fiqh dikatakan sebagai hasil akhir dari suatu proses dialogis dan dialektis antara pesan-pesan samawi (normativitas) dengan kondisi aktual bumi (historisitas). Aturan-aturan yang terbukukan dalam berbagai kitab fiqh tidak dapat dilepaskan dari pengaruh cara pandang manusia, baik secara pribadi maupun sosial. Dengan demikian, selain sarat dengan nilai teologis, fiqh juga memiliki watak sosiologis.[14]

Dengan penjelasan di atas, fiqh berarti dapat membentuk dan dibentuk oleh masyarakat. Hubungan yang saling mengisi ini menunjukkan betapa dominan muatan kultural dalam fiqh itu. Kuatnya muatan kultural itu dapat dibuktikan dengan keterbukaan fiqh untuk menerima konsep ‘urf, istihsan serta istislah sebagai bagian dari sumber-sumber fiqh.[15]

Ada beberapa bukti kesejarahan lainnya untuk menunjukkan bagaimana kondisi sosial budaya memberikan pengaruh kuat terhadap pembentukan fiqih. Adanya qaul jadid dari Imam Syafi’i yang dikompilasikan setelah sampainya ia di Mesir, ketika dikontraskan dengan qaul qadim-nya yang dikompilasikan di Irak, merefleksikan adanya pengaruh dari tradisi adat kedua negeri yang berbeda.[16] Imam Malik percaya bahwa aturan adat dari suatu negeri harus dipertimbangkan dalam memformulasikan suatu ketetapan, walaupun ia memandang adat atau ‘amal ahl al-Madinah sebagai variabel yang paling otoritatif dalam teori hukumnya, merupakan bukti lain dari kuatnya pengaruh kultur setempat tidak pernah dikesampingkan oleh para juris muslim dalam usahanya untuk membangun hukum. Bagi Malik ‘Amal ahli Madinah ini lebih kuat dari hadis Ahad (transmisi tunggal). “Al-‘amal atsbat min al-hadits”, katanya. Pendirian Malik yang menghargai tradisi lokal Madinah tersebut terus dipertahankan meski banyak ulama yang menentangnya dan meski harus berhadapan dengan rezim yang berkuasa. Pada suatu saat, Khalifah Abbasiyah Abu Ja’far al-Manshur, memintanya agar kitab Muwattha’ yang menghimpun hadits-hadits Nabi karyanya dijadikan sumber hukum positif yang akan diberlakukan diseluruh wilayah Islam. Imam Malik menolak, katanya: “ Anda tahu bahwa diberbagai wilayah negeri ini telah berkembang berbagi tradisi hukum sesuai dengan tuntutan kemaslahatan setempat. Biarkan masyarakat memilih sendiri panutannya. Saya kira tidak ada alasan untuk menyeragamkannya. Tidak ada seorangpun yang berhak secara eklusif mengklaim kebenaran atas namaTuhan”.[17]

Dalam konteks Indonesia lahirnya KHI (Kompilasi Hukum Islam) yang didalamnya juga diadopsi sistem gono-gini merupakan bentuk dialektika hukum islam dengan tradisi yang berkembang di Indonesia. Ini merupakan cita-cita lama dari para pemikir hukum islam di Indonesia yang menginginkan adanya fiqh yang berkepribadian Indonesia, seperti Hasbi Ash-Shiddieqi ataupun Hazairin.[18]

Fenomena yang disebut terakhir ini menunjukkan bahwa fiqh Islam adalah hukum yang hidup dan berkembang, yang mampu bergumul dengan persoalan-persoalan lokal yang senantiasa meminta etik dan paradigma baru. Keluasan hukum Islam adalah satu bukti dari adanya ruang gerak dinamis itu. Ia merupakan implementasi obyektif dari doktrin Islam yang meskipun berdiri di atas kebenaran mutlak dan kokoh, juga memiliki ruang gerak dinamis bagi perkembangan, pembaharuan dan kehidupan sesuai dengan fleksibilitas ruang dan waktu.

Besarnya adanya akulturasi timbal balik antara Islam dan budaya lokal diakui juga dalam suatu kaedah atau ketentuan dasar dalam ilmu usul al-fiqh, bahwa “adat itu dihukumkan” (al-adah muhakkamah), atau lebih lengkapnya, “ Adat adalah syari’ah yng dihukumkan” (al-adah syari’ah muhakkamah). Artinya, adat dan kebiasaan suatu masyarakat, yaitu budaya lokalnya, adalah sumber hukum dalam Islam. [19]

Islam sebagai agama yang universal yang melintasi batas ruang dan waktu kadangkala bertemu dengan tradisi lokal yang berbeda-beda. Ketika Islam bertemu dengan tradisi lokal, wajah Islam berbeda dari tempat satu dengan lainnya. Menyikapi masalah ini ada dua hal yang penting disadari. Pertama, Islam itu sebenarnya lahir sebagai produk lokal yang kemudian diuniversalisasikan dan ditransendensi, sehingga kemudian menjadi universal. Dalam konteks arab, yang dimaksud dengan Islam sebagai produk lokal adalah Islam yang lahir di Arab, tepatnya daerah Hijaz, dalam situasi Arab dan pada waktu itu ditujukan sebagai jawaban terhadap persoalan-persoalan yang berkembang disana. Islam arab tersebut terus berkembang ketika bertemu dengan budaya dan peradaban Persia dan Yunani, sehingga kemudian Islam mengalami proses dinamisasi kebudayaan dan peradaban.

Kedua, walaupun kita yakin bahwa Islam itu wahyu Tuhan yang universal, yang gaib, namun akhirnya ia dipersepsi oleh sipemeluk sesuai dengan pengalaman, problem, kapasitas, intelektual, sistem budaya, dan segala keragaman masing-masing pemeluk didalam komunitasnya. Dengan demikian, memang justru kedua dimensi ini perlu disadari yang disatu sisi Islam sebagai universal, sebagai kritik terhadap budaya lokal, dan kemudian budaya lokal sebagai bentuk kearifan (local wisdom) masing-masing pemeluk di dalam memahami dan menerapkan Islam itu.

Berkaitan dengan itu, Syah Waliyullah al-Dahlawi, pemikir Islam India mengemukakan adanya Islam universal dan Islam lokal. Ajaran tentang Tauhid (pengesaan Tuhan) adalah universal yang harus menembus batas-batas geografis dan kultural yang tidak dapat ditawar-tawar lagi. Sementara itu ekspresi kebudayaan dalam bentuk tradisi, cara berpakaian, arsitektur, sastra dan lain-lain memiliki muatan lokal yang tidak selalu sama.

DAFTAR PUSTAKA

Abdullahi Ahmed an-Na’im, Islam dan Negara Sekuler: Menegosiasikan Masa Depan Syari’ah (Bandung: Mizan, 2007).

Fawaizul Umam dkk, Membangun Resistensi. Merawat Tradisi: Modal Sosial Komunitas Wetu Telu (Mataram: LkiM, 2007)

Fawaizul Umam,Dari Terma ke Stigma: Geneologi Islam Weru Telu Lombok NTB, Jurnal Istiqro’, Jurnal Penelitian Direktorat Perguruan Tinggi Agama Islam, Volume 04, Nomor 01, 2005

[1] Balairung No. 26/TH.XII/1997, hlm. 76.

[1] Solichin Salam, Lombok Pulau Perawan (Jakarta: Kuning Mas, 1992), hlm. 8-12.

Erni Budiwanti,”The Impact of Islam on the Religion of the Sasak in Bayan, West Lombok” dalam Kultur Volume I, No.2/2001/hlm. 30.

[1] John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim: Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak, terj. Imron Rosyadi (Yogyakarta: Tiara wacana, 2001), hlm. 86.

[1] Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak; Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima, terj. Noorcholis dan Hairus Salim (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm. 1.

Mark R. Woodward, Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan, terj. Hairus Salim HS (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2004).

[1] Penganut Islam Wetu Telu tidak hanya di Bayan (Lombok Barat), tetapi juga di daerah lombok Tengah (Sengkol).Lihat Asnawi, Respon Kultural Masyarakat Sasak Terhadap Islam, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 11. Lihat Juga Fathurrahman Zakaria, Mozaik Budaya Orang Mataram (Mataram: Yayasan Sumurmas Al-Hamidy, 1998),hlm. 158.

Zaki Yamani Athar, Kearifan Lokal Dalam Ajaran Islam Wetu Telu di Lombok, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 76.

[1] Ahmad Zainul Hamdi, “Islam Lokal; Ruang Perjumpaan Universalitas dan Lokalitas” Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 122-123.

[1] Amin Syukur, “Fiqh dalam Rentang Sejarah”, dalam Noor Ahmad dkk, Epistemologi Syara’; Mencari Format Baru Fiqh Indonesia (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2000), hlm. X.

Marzuki Wahid dan Rumadi, Fiqh Madzhab Negara (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2001), hlm. 81.

[1] Ratno Lukito, Pergumulan Antara Hukum Islam Dan Adat di Indonesia (Jakarta: INIS, 1998),

Imam Syafi’i baca Jaih Mubarok, Modifikasi Hukum Islam; Studi Tentang Qawl Qadim dan Qawl Jadid (Jakarta: Raja Grafindo Persada, 2002).

Husein Muhammad, Spiritualitas Kemanusiaan Perspektif Islam Pesantren (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Rihlah, 2006), hlm.159.

[1] Nurcholish Madjid, “Islam dan Budaya Lokal: Masalah Akulturasi Timbal Balik”, dalam Islam Doktrin dan Peradaban (Jakarta: Paramadina, 1992) hlm. 542-554.

Yudian Wahyudi, Hasbi’s Theory of Ijtihad in the Context of Indonesian Fiqh (Yogyakarta: Nawesea, 2007)

Yudian W. Asmin, Catatan Editor, dalam Yudian (ed) “Ke Arah Fiqh Indonesia”, (Yogyakarta: Forum Studi Hukum Islam, 1994).

[1] Balairung No. 26/TH.XII/1997, hlm. 76.

[2] Solichin Salam, Lombok Pulau Perawan (Jakarta: Kuning Mas, 1992), hlm. 8-12.

[3] Boda merupakan kepercayaan asli orang Sasak sebelum kedatangan pengaruh asing. Orang Sasak pada waktu itu, yang menganut kepercayaan ini, disebut Sasak Boda. Agama Sasak Boda ini ditandai oleh Animisme dan Panteisme. Pemujaan dan Penyembahan roh-roh leluhur dan berbagai dewa lokal lainnya merupakan fokus utama dari praktek keagamaan Sasak Boda. Lihat Erni Budiwanti,”The Impact of Islam on the Religion of the Sasak in Bayan, West Lombok” dalam Kultur Volume I, No.2/2001/hlm. 30.

[4] Kebenaran reputasi ini bisa kita uji dengan melihat praktik keagamaan di Lombok. Menurut pengamatan penulis selama ini ternyata siang-malam penuh dengan ritual keagamaan (apalagi pada bulan-bulan penting). Siang hari di setiap sudut desa mesti kita akan menemukan Tuan Guru sedang memberikan pengajian keagamaan, sedangkan pada malam hari, dari masjid-masjid maupun Langgar-Langgar terdengar sekelompok orang (jamaah) baca Hizib, Barzanji maupun amalan-amalan sunnah lainnya.

[5] John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim: Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak, terj. Imron Rosyadi (Yogyakarta: Tiara wacana, 2001), hlm. 86.

[6] Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak; Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima, terj. Noorcholis dan Hairus Salim (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm. 1.

[7] Secara geografis, pulau Lombok terletak antara dua pulau yaitu sebelah barat berbatasan dengan Pulau Bali (daerah wisata), sedangkan sebelah timur berbatasan dengan Pulau Sumbawa, yang terkenal dengan “Susu kuda liar” dan “Madu Sumbawa”. Penduduk asli Lombok adalah susu sasak yang merupakan kelompok etnik mayoritas Lombok (90 %), sisanya adalah Bali, Sumbawa, Jawa, Arab, Cina dll. Dari segi agama mayoritas beragama Islam (waktu lima dan Wetu Telu), Hindu,Budha dan Kristen. Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak:Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm.6

[8] Corak Islam Jawa adalah corak keislaman yang sejak dini ditanam di Jawa oleh para Wali. Para wali menyemai orientasi keislaman yang memadukan antara syari’ah dan tasawuf. Orientasi inilah yang memungkinkan kalangan Islam tradisional Jawa mampu mengapresiasi lokalitas tanpa harus mengkhianati prinsip dasar Islam. Karena itu, maka tidak mengherankan jika Woodward kecele ketika melakukan studi tentang Islam Jawa. Karena pengaruh wacana dominan bahwa Islam Jawa sangat dipengaruhi Hindu, maka salah satu persiapan penting yang ia lakukan sebelum melakukan penelitian di Jawa adalah mempelajari doktrin-doktrin agama Hindu. Namun apa yang terjadi? Dia sama sekali tidak menemukan bukti bahwa apa yang dituduhkan selama ini terhadap Islam Jawa sebagai warisan Hindu bisa ditemukan dalam ajaran-ajaran skriptualis Hinduisme. Lihat Mark R. Woodward, Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan, terj. Hairus Salim HS (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2004).

[9] Penganut Islam Wetu Telu tidak hanya di Bayan (Lombok Barat), tetapi juga di daerah lombok Tengah (Sengkol).Lihat Asnawi, Respon Kultural Masyarakat Sasak Terhadap Islam, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 11. Lihat Juga Fathurrahman Zakaria, Mozaik Budaya Orang Mataram (Mataram: Yayasan Sumurmas Al-Hamidy, 1998),hlm. 158.

[10] Erni Budiwanti, Islam..., hlm. 136. Juga John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim; Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak (Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 2001), hlm.98.

[11] Zaki Yamani Athar, Kearifan Lokal Dalam Ajaran Islam Wetu Telu di Lombok, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 76.

[12] Fawaizul Umam dkk, Membangun Resistensi. Merawat Tradisi: Modal Sosial Komunitas Wetu Telu (Mataram: LKiM, 2007)

[13] Ahmad Zainul Hamdi, “Islam Lokal; Ruang Perjumpaan Universalitas dan Lokalitas” Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 122-123.

[14] Amin Syukur, “Fiqh dalam Rentang Sejarah”, dalam Noor Ahmad dkk, Epistemologi Syara’; Mencari Format Baru Fiqh Indonesia (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2000), hlm. X.

[15] Karena secara sosiologis dan kultural, hukum Islam adalah hukum yang mengalir dan berurat berakar pada budaya masyarakat. Hal tersebut disebabkan karena fleksibelitas dan elastisitas yang dimiliki hukum Islam. Artinya, kendatipun hukum Islam tergolong hukum yang otonom –karena adanya otoritas Tuhan di dalamnya— akan tetapi dalam tataran implementasinya ia sangat aplicable dan acceptable dengan berbagai jenis budaya lokal. Karena itu, bisa dipahami bila dalam sejarahnya di sebagian daerah ia mampu menjadi kekuatan moral masyarakat (moral force of people) dalam berdialektika dengan realitas kehidupan. Baca Marzuki Wahid dan Rumadi, Fiqh Madzhab Negara (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2001), hlm. 81.

[16] Ratno Lukito, Pergumulan Antara Hukum Islam Dan Adat di Indonesia (Jakarta: INIS, 1998), hlm. 19. Kajian lebih lengkap tentang qaul qadim dan qaul al-jadid-nya Imam Syafi’i baca Jaih Mubarok, Modifikasi Hukum Islam; Studi Tentang Qawl Qadim dan Qawl Jadid (Jakarta: Raja Grafindo Persada, 2002). Lihat juga Hafizh A. Masro, “Perubahan Hukum Islam (Suatu Analisis Sosiologi Atas Pendirian Asy-Syafi’i)” dalam Al-Mawarid, Edisi Ketiga 1995,hlm. 12-22.

[17] Husein Muhammad, Spiritualitas Kemanusiaan Perspektif Islam Pesantren (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Rihlah, 2006), hlm.159.

[18] Untuk pemikiran Hasbi baca Yudian Wahyudi, Hasbi’s Theory of Ijtihad in the Context of Indonesian Fiqh (Yogyakarta: Nawesea, 2007). Tentang Hazairin baca Hazairin, Hendak kemana Hukum Islam (Jakarta: Tintamas, 1976). Juga Mahsun Fuad, Hukum Islam Indonesia (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2005).

[19] Nurcholish Madjid, “Islam dan Budaya Lokal: Masalah Akulturasi Timbal Balik”, dalam Islam Doktrin dan Peradaban (Jakarta: Paramadina, 1992) hlm. 542-554.

http://klik-dunk.blogspot.com/2008/12/pergumulan-islam-dan-budaya-sasak.html

Dua kawasan lainnya, yakni Lombok Tengah dan Lombok Timur juga diwarnai kondisi yang berbeada. Lombok Tengah adalah daerah miskin tanahnya kurang subur. Sedangkan Lombok Timur terhitung sedikit lebih subur jika dibanding Lombpok Tengah karena kawasannya yang terletak di dataran tinggi Gunung Rinjani (Gunung tergolong Merapi aktif di Lombok). Dua kawasan inilah yang di masa lalu menjadi benteng Islamisasi kerajaan Islam Jawa di kawasan timur nusantara. [2]

Pengaruh Kerajaan inilah yang kemungkinan menyebabkan Islam menjadi agama mayoritas suku asli Lombok sekarang ini. Tetapi klaim ini masih perlu diuji kembali, karena masuknya Islam di Lombok belum di ketahui secara pasti. Akan tetapi diperkirakan pada abad ke-16 yang di bawa oleh Sunan Prapen, Putera dari Sunan Giri, salah seorang Wali Songo di Jawa.

Dalam perkembangan selanjutnya, Islam merupakan dan menjadi sebuah faktor utama dalam masyarakat Lombok. Hampir 95 % dari penduduk kepulauan itu adalah orang Sasak dan hampir semuanya adalah muslim. Seorang etnografis bahkan jauh mengatakan bahwa “menjadi Sasak berarti menjadi muslim”. Meskipun pernyataan ini tidak seluruhnya benar (karena pernyataan ini mengabaikan popularitas Sasak Boda),[3] sentimen-sentimen itu dipegangi bersama oleh sebagian besar penduduk Lombok karena identitas Sasak begitu erat terkait dengan identitas mereka sebagai muslim.

Bila lombok dicap sebagai “sebuah pulau dengan 1000 masjid” yang mungkin meremehkan keberadaan sejumlah masjid kecil di Pulau tersebut, pesannya adalah jelas. Lombok sangat terkenal di Indonesia sebagai sebuah tempat di mana Islam diterima secara serius dan tipe Islam yang dipraktekkan adalah pada umumnya adalah agak kaku dan bentuknya ortodoks bila dibandingkan dengan di daerah lain di negeri ini.[4] Islam sebagaimana ia di praktekkan dan di pahami di Lombok menampilkan sejumlah variasi yang signifikan. Dalam tradisi keislaman masyarakat Sasak akan ditemukan dua varian Islam yaitu “Islam Wetu Telu ” dan “Islam Waktu Lima ”.[5]

Wetu Telu adalah orang sasak yang, meskipun mengaku sebagai muslim, masih sangat percaya terhadap ketuhanan animistik leluhur (ancestral animistic deitis) maupun benda-benda antropomorfis (anthropomorphised inanimate objects). Dalam hal itu mereka adalah panteis. Sebaliknya, waktu lima adalah orang muslim sasak yang mengikuti ajaran syari’ah secara lebih keras sebagaimana diajarkan oleh al-Qur’an dan Hadis. Mengikuti dikotomi Geertz dalam Religion of Java, agama wetu telu lebih mirip dengan Islam abangan yang sinkretik, walaupun waaktu lima tidaklah seperti bentuk Islam santri.[6]

Yang unik dari praktik keagamaan atau ibadah Wetu Telu adalah adanya perbedaan tata cara ibadah yang berbeda-beda antara daerah satu dengan lainnya. Di Sembalun daerah dingin Leren Gunung Rinjani (Lombok Timur), mereka hanya menjalankan solat Ashar pada

Islam Sasak (Islam Wetu Telu): Wujud Dialektika Islam Dengan Budaya Sasak

Agama sasak atau lebih spesifik lagi Islam sasak merupakan cermin dari pergulatan agama lokal atau tradisional berhadapan dengan agama dunia yang universal dalam hal ini Islam. Seperti yang terjadi di Bayan (Lombok), [7] Islam Wetu Telu (Islam Lokal) yang banyak dipeluk oleh penduduk Sasak asli dianggap sebagai “tata cara keagamaan Islam yang salah (bahkan cenderung syirik)” oleh kalangan Islam Waktu lima, sebuah varian Islam universal yang dibawa oleh orang-orang dari daerah lain di Lombok. Tak pelak, Islam waktu lima sejak awal kehadirannya disengaja untuk melakukan misi atau dakwah Islamiyah terhadap kalangan Wete Telu.

Secara sederhana barangkali dapat dikatakan bahwa Wetu Telu merupakan sejenis Islam yang dijalankan dengan tradisi-tradisi lokal dan adat sasak. Varian Islam ini lebih mirip dengan Islam abangan atau Islam Jawa di Jawa, seperti yang ditulis Mark Woodward dalam buku “Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan”.[8] Dalam agama wetu Telu, yang paling menonjol dan sentral adalah pengetahuan tentang lokal, tentang adat, bukan pengetahuan tentang sebagai rumusan doktrin yang datang dari Arab.Akan tetapi juga bukan tidak menggunakan Islam sama sekali, dalam doa-doa, temapat peribadatan masjid dan beberapa praktek ibadah lain, merupakan introduksi keislaman mereka.

Penyebutan istilah Wetu Telu mempunyai perspektif yang berbeda-beda. Komunitas Waktu Lima menyatakan bahwa Wetu Telu sebagai waktu tiga (tiga:telu) dan mengaitkan makna ini dengan reduksi seluruh ibadah Islam menjadi tiga. Orang Bayan[9] sebagai penganut terbesar Islam Wetu Telu ini, menolak penafsiran semacam itu. Pemangku Adatnya mengatakan bahwa, term wetu sering dikacaukan dengan waktu. Wetu berasal dari kata “metu” yang berarti “muncul” atau “datang dari”. Sedangkan “telu” artinya “tiga”. Secara simbolis makna ini mengungkapkan bahwa semua makhluk hidup muncul melalui tiga macam sistem reproduksi, yaitu melahirkan (disebut menganak), bertelur (disebut menteluk) dan berkembang biak dari benih (disebut juga mentiuk). Term Wetu Telu juga tidak hanya menunjuk kepada tiga macam sistem reproduksi, tetapi juga menunjuk pada kemahakuasaan Tuhan yang memungkinkan makhluk hidup untuk hidup dan mengembangkan diri melalui mekanisme reproduksi tersebut.[10] Sumber lain menyebutkan bahwa ungkapan Wetu Telu berasal dari bahasa Jawa yaitu Metu Saking Telu yakni keluar atau bersumber dari tiga hal: Al-Qur’an, Hadis dan Ijma. Artinya, ajaran-ajaran komunitas penganut Islam Wetu Telu bersumber dari ketiga sumber tersebut.[11]

Komunitas Islam Wetu Telu ini dalam perjalanannya mulai terdesak sedikit demi sedikit oleh arus modernitas, ortodoksisme Islam dan “serangan” dakwah terus menerus yang dilakukan oleh Islam Waktu Lima ( jenis Islam puritan yang ada di Lombok), serta implikasi massif dari kebijakan politik terutama proyek transmigrasi lokal ke kawasan adat mereka.[12] Mengapa selalu termarginalkan nasib keyakinan Islam yang bernuansa lokal? Bukankah ini justru bukti pluralitas keagamaan dalam Islam sendiri, yang menunjukkan keramahannya terhadap budaya lokal.Padahal beralihnya Orang Sasak dari Boda (sinkretisme Hindu-Budha) menjadi Islam, kemudian dari muslim sinkretis dan nominal –disebut Wetu Telu- menjadi Islam yang sempurna –Waktu Lima- memperlihatkan dinamisme kultural dalam cara Islam disebarkan, kemudian diserap, diakomodasi dan diekspresikan di Indonesia. Dinamisme kultural juga melatari fakta bahwa aktifitas penyebaran dan penanaman ajaran Islam merupakan proses panjang dan berkesinambungan dalam antagonisme dan asimilasi tiada henti.

Lepas dari berbagai stigma yang dilekatkan pada Islam lokal (seperti Jawa dan Sasak) ada baiknya menyimak pendapat Eickelman bahwa melihat Islam lokal dengan melepas kaitannya dengan Islam normatif adalah sebuah pandangan yang gagal melihat fakta betapa kebanyakan kaum muslim menjadikan normativitas Islam sebagai esensi untuk memaknai praktik dan keyakinan Islamnya. Dalam konteks ini,adalah menarik melihat penolakan Braten terhadap pandangan Geertz. Braten mengawalinya dengan sebuah penelitian di salah satu desa yang dikenal kuat Islamnya di wilayah Jawa, tepatan di Desa Batasan, kabupaten Semarang. Desa tersebut terkenal yang sangat fanatik Islamnya terutama NU. Berdasarkan spirit harmoni yang membentuk sikap hidup masyarakat Jawa, Braten menemukan bahwa dakwah Islam sama sekali tidak dilakukan dengan melangsungkan oposisi terhadap tradisi lokal. Sekali lagi bahwa ini bukan dengan mengorbankan Islam atau mengorbankan tradisi, tapi mewarnai tradisi dengan spirit Islam. Bacaan Bismillah menjadi pembuka bagi seluruh akatifitas kemasyarakatan. Masyarakat bahkan memiliki caranya sendiri untuk tetap menjaga harmoni itu. Mereka tahu bahwa adat tetap dilakukan dengan tanpa mencederai jiwa Islam. Sementara Islam dilakukan dengan tetap menjaga harmoni tradisi masyarakat. Oleh sebab itu, yang terpenting bahwa tuduhan bahwa praktik-praktik Islam lokal, seperti Jawa dan Sasak, semata-mata bersifat animis-hindu-budhis dan tidak memiliki landasannya secara normatif dalam doktrin Islam, patut dipertanyakan ulang. Apa yang selama ini dianggap sebagai kepercayaan dan praktik Islam lokal nyatanya juga dipraktikkan oleh banyak kaum muslim di belahan dunia lain. Untuk konteks nusantara, ia hadir mengemuka bersama dengan proses panjang islamisasi ini sendiri.[13]

Aspek Lokalitas dalam Fiqh Islam

Salah satu disiplin keilmuan Islam yang menjadi fakta sejarah bagaimana doktrin Islam mengaprisiasi budaya lokal adalah ilmu fiqih. Sebagai institusi pembebas, fiqh harus dimaknai proses bukan produk monumental. Hukum Islam atau fiqh, memiliki karakteristik yang jauh berbeda dengan hukum dalam pengertian ilmu hukum modern. Hukum Islam dikembangkan berdasarkan wahyu di samping pemikiran manusia dan juga diwarnai oleh ciri kelokalan di samping ciri keuniversalan. Dengan demikian, fiqh dikatakan sebagai hasil akhir dari suatu proses dialogis dan dialektis antara pesan-pesan samawi (normativitas) dengan kondisi aktual bumi (historisitas). Aturan-aturan yang terbukukan dalam berbagai kitab fiqh tidak dapat dilepaskan dari pengaruh cara pandang manusia, baik secara pribadi maupun sosial. Dengan demikian, selain sarat dengan nilai teologis, fiqh juga memiliki watak sosiologis.[14]

Dengan penjelasan di atas, fiqh berarti dapat membentuk dan dibentuk oleh masyarakat. Hubungan yang saling mengisi ini menunjukkan betapa dominan muatan kultural dalam fiqh itu. Kuatnya muatan kultural itu dapat dibuktikan dengan keterbukaan fiqh untuk menerima konsep ‘urf, istihsan serta istislah sebagai bagian dari sumber-sumber fiqh.[15]

Ada beberapa bukti kesejarahan lainnya untuk menunjukkan bagaimana kondisi sosial budaya memberikan pengaruh kuat terhadap pembentukan fiqih. Adanya qaul jadid dari Imam Syafi’i yang dikompilasikan setelah sampainya ia di Mesir, ketika dikontraskan dengan qaul qadim-nya yang dikompilasikan di Irak, merefleksikan adanya pengaruh dari tradisi adat kedua negeri yang berbeda.[16] Imam Malik percaya bahwa aturan adat dari suatu negeri harus dipertimbangkan dalam memformulasikan suatu ketetapan, walaupun ia memandang adat atau ‘amal ahl al-Madinah sebagai variabel yang paling otoritatif dalam teori hukumnya, merupakan bukti lain dari kuatnya pengaruh kultur setempat tidak pernah dikesampingkan oleh para juris muslim dalam usahanya untuk membangun hukum. Bagi Malik ‘Amal ahli Madinah ini lebih kuat dari hadis Ahad (transmisi tunggal). “Al-‘amal atsbat min al-hadits”, katanya. Pendirian Malik yang menghargai tradisi lokal Madinah tersebut terus dipertahankan meski banyak ulama yang menentangnya dan meski harus berhadapan dengan rezim yang berkuasa. Pada suatu saat, Khalifah Abbasiyah Abu Ja’far al-Manshur, memintanya agar kitab Muwattha’ yang menghimpun hadits-hadits Nabi karyanya dijadikan sumber hukum positif yang akan diberlakukan diseluruh wilayah Islam. Imam Malik menolak, katanya: “ Anda tahu bahwa diberbagai wilayah negeri ini telah berkembang berbagi tradisi hukum sesuai dengan tuntutan kemaslahatan setempat. Biarkan masyarakat memilih sendiri panutannya. Saya kira tidak ada alasan untuk menyeragamkannya. Tidak ada seorangpun yang berhak secara eklusif mengklaim kebenaran atas namaTuhan”.[17]

Dalam konteks Indonesia lahirnya KHI (Kompilasi Hukum Islam) yang didalamnya juga diadopsi sistem gono-gini merupakan bentuk dialektika hukum islam dengan tradisi yang berkembang di Indonesia. Ini merupakan cita-cita lama dari para pemikir hukum islam di Indonesia yang menginginkan adanya fiqh yang berkepribadian Indonesia, seperti Hasbi Ash-Shiddieqi ataupun Hazairin.[18]

Fenomena yang disebut terakhir ini menunjukkan bahwa fiqh Islam adalah hukum yang hidup dan berkembang, yang mampu bergumul dengan persoalan-persoalan lokal yang senantiasa meminta etik dan paradigma baru. Keluasan hukum Islam adalah satu bukti dari adanya ruang gerak dinamis itu. Ia merupakan implementasi obyektif dari doktrin Islam yang meskipun berdiri di atas kebenaran mutlak dan kokoh, juga memiliki ruang gerak dinamis bagi perkembangan, pembaharuan dan kehidupan sesuai dengan fleksibilitas ruang dan waktu.

Besarnya adanya akulturasi timbal balik antara Islam dan budaya lokal diakui juga dalam suatu kaedah atau ketentuan dasar dalam ilmu usul al-fiqh, bahwa “adat itu dihukumkan” (al-adah muhakkamah), atau lebih lengkapnya, “ Adat adalah syari’ah yng dihukumkan” (al-adah syari’ah muhakkamah). Artinya, adat dan kebiasaan suatu masyarakat, yaitu budaya lokalnya, adalah sumber hukum dalam Islam. [19]

Islam sebagai agama yang universal yang melintasi batas ruang dan waktu kadangkala bertemu dengan tradisi lokal yang berbeda-beda. Ketika Islam bertemu dengan tradisi lokal, wajah Islam berbeda dari tempat satu dengan lainnya. Menyikapi masalah ini ada dua hal yang penting disadari. Pertama, Islam itu sebenarnya lahir sebagai produk lokal yang kemudian diuniversalisasikan dan ditransendensi, sehingga kemudian menjadi universal. Dalam konteks arab, yang dimaksud dengan Islam sebagai produk lokal adalah Islam yang lahir di Arab, tepatnya daerah Hijaz, dalam situasi Arab dan pada waktu itu ditujukan sebagai jawaban terhadap persoalan-persoalan yang berkembang disana. Islam arab tersebut terus berkembang ketika bertemu dengan budaya dan peradaban Persia dan Yunani, sehingga kemudian Islam mengalami proses dinamisasi kebudayaan dan peradaban.

Kedua, walaupun kita yakin bahwa Islam itu wahyu Tuhan yang universal, yang gaib, namun akhirnya ia dipersepsi oleh sipemeluk sesuai dengan pengalaman, problem, kapasitas, intelektual, sistem budaya, dan segala keragaman masing-masing pemeluk didalam komunitasnya. Dengan demikian, memang justru kedua dimensi ini perlu disadari yang disatu sisi Islam sebagai universal, sebagai kritik terhadap budaya lokal, dan kemudian budaya lokal sebagai bentuk kearifan (local wisdom) masing-masing pemeluk di dalam memahami dan menerapkan Islam itu.

Berkaitan dengan itu, Syah Waliyullah al-Dahlawi, pemikir Islam India mengemukakan adanya Islam universal dan Islam lokal. Ajaran tentang Tauhid (pengesaan Tuhan) adalah universal yang harus menembus batas-batas geografis dan kultural yang tidak dapat ditawar-tawar lagi. Sementara itu ekspresi kebudayaan dalam bentuk tradisi, cara berpakaian, arsitektur, sastra dan lain-lain memiliki muatan lokal yang tidak selalu sama.

DAFTAR PUSTAKA

Abdullahi Ahmed an-Na’im, Islam dan Negara Sekuler: Menegosiasikan Masa Depan Syari’ah (Bandung: Mizan, 2007).

Fawaizul Umam dkk, Membangun Resistensi. Merawat Tradisi: Modal Sosial Komunitas Wetu Telu (Mataram: LkiM, 2007)

Fawaizul Umam,Dari Terma ke Stigma: Geneologi Islam Weru Telu Lombok NTB, Jurnal Istiqro’, Jurnal Penelitian Direktorat Perguruan Tinggi Agama Islam, Volume 04, Nomor 01, 2005

[1] Balairung No. 26/TH.XII/1997, hlm. 76.

[1] Solichin Salam, Lombok Pulau Perawan (Jakarta: Kuning Mas, 1992), hlm. 8-12.

Erni Budiwanti,”The Impact of Islam on the Religion of the Sasak in Bayan, West Lombok” dalam Kultur Volume I, No.2/2001/hlm. 30.

[1] John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim: Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak, terj. Imron Rosyadi (Yogyakarta: Tiara wacana, 2001), hlm. 86.

[1] Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak; Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima, terj. Noorcholis dan Hairus Salim (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm. 1.

Mark R. Woodward, Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan, terj. Hairus Salim HS (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2004).

[1] Penganut Islam Wetu Telu tidak hanya di Bayan (Lombok Barat), tetapi juga di daerah lombok Tengah (Sengkol).Lihat Asnawi, Respon Kultural Masyarakat Sasak Terhadap Islam, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 11. Lihat Juga Fathurrahman Zakaria, Mozaik Budaya Orang Mataram (Mataram: Yayasan Sumurmas Al-Hamidy, 1998),hlm. 158.

Zaki Yamani Athar, Kearifan Lokal Dalam Ajaran Islam Wetu Telu di Lombok, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 76.

[1] Ahmad Zainul Hamdi, “Islam Lokal; Ruang Perjumpaan Universalitas dan Lokalitas” Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 122-123.

[1] Amin Syukur, “Fiqh dalam Rentang Sejarah”, dalam Noor Ahmad dkk, Epistemologi Syara’; Mencari Format Baru Fiqh Indonesia (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2000), hlm. X.

Marzuki Wahid dan Rumadi, Fiqh Madzhab Negara (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2001), hlm. 81.

[1] Ratno Lukito, Pergumulan Antara Hukum Islam Dan Adat di Indonesia (Jakarta: INIS, 1998),

Imam Syafi’i baca Jaih Mubarok, Modifikasi Hukum Islam; Studi Tentang Qawl Qadim dan Qawl Jadid (Jakarta: Raja Grafindo Persada, 2002).

Husein Muhammad, Spiritualitas Kemanusiaan Perspektif Islam Pesantren (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Rihlah, 2006), hlm.159.

[1] Nurcholish Madjid, “Islam dan Budaya Lokal: Masalah Akulturasi Timbal Balik”, dalam Islam Doktrin dan Peradaban (Jakarta: Paramadina, 1992) hlm. 542-554.

Yudian Wahyudi, Hasbi’s Theory of Ijtihad in the Context of Indonesian Fiqh (Yogyakarta: Nawesea, 2007)

Yudian W. Asmin, Catatan Editor, dalam Yudian (ed) “Ke Arah Fiqh Indonesia”, (Yogyakarta: Forum Studi Hukum Islam, 1994).

[1] Balairung No. 26/TH.XII/1997, hlm. 76.

[2] Solichin Salam, Lombok Pulau Perawan (Jakarta: Kuning Mas, 1992), hlm. 8-12.

[3] Boda merupakan kepercayaan asli orang Sasak sebelum kedatangan pengaruh asing. Orang Sasak pada waktu itu, yang menganut kepercayaan ini, disebut Sasak Boda. Agama Sasak Boda ini ditandai oleh Animisme dan Panteisme. Pemujaan dan Penyembahan roh-roh leluhur dan berbagai dewa lokal lainnya merupakan fokus utama dari praktek keagamaan Sasak Boda. Lihat Erni Budiwanti,”The Impact of Islam on the Religion of the Sasak in Bayan, West Lombok” dalam Kultur Volume I, No.2/2001/hlm. 30.

[4] Kebenaran reputasi ini bisa kita uji dengan melihat praktik keagamaan di Lombok. Menurut pengamatan penulis selama ini ternyata siang-malam penuh dengan ritual keagamaan (apalagi pada bulan-bulan penting). Siang hari di setiap sudut desa mesti kita akan menemukan Tuan Guru sedang memberikan pengajian keagamaan, sedangkan pada malam hari, dari masjid-masjid maupun Langgar-Langgar terdengar sekelompok orang (jamaah) baca Hizib, Barzanji maupun amalan-amalan sunnah lainnya.

[5] John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim: Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak, terj. Imron Rosyadi (Yogyakarta: Tiara wacana, 2001), hlm. 86.

[6] Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak; Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima, terj. Noorcholis dan Hairus Salim (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm. 1.

[7] Secara geografis, pulau Lombok terletak antara dua pulau yaitu sebelah barat berbatasan dengan Pulau Bali (daerah wisata), sedangkan sebelah timur berbatasan dengan Pulau Sumbawa, yang terkenal dengan “Susu kuda liar” dan “Madu Sumbawa”. Penduduk asli Lombok adalah susu sasak yang merupakan kelompok etnik mayoritas Lombok (90 %), sisanya adalah Bali, Sumbawa, Jawa, Arab, Cina dll. Dari segi agama mayoritas beragama Islam (waktu lima dan Wetu Telu), Hindu,Budha dan Kristen. Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak:Wetu Telu Versus Waktu Lima (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2000), hlm.6

[8] Corak Islam Jawa adalah corak keislaman yang sejak dini ditanam di Jawa oleh para Wali. Para wali menyemai orientasi keislaman yang memadukan antara syari’ah dan tasawuf. Orientasi inilah yang memungkinkan kalangan Islam tradisional Jawa mampu mengapresiasi lokalitas tanpa harus mengkhianati prinsip dasar Islam. Karena itu, maka tidak mengherankan jika Woodward kecele ketika melakukan studi tentang Islam Jawa. Karena pengaruh wacana dominan bahwa Islam Jawa sangat dipengaruhi Hindu, maka salah satu persiapan penting yang ia lakukan sebelum melakukan penelitian di Jawa adalah mempelajari doktrin-doktrin agama Hindu. Namun apa yang terjadi? Dia sama sekali tidak menemukan bukti bahwa apa yang dituduhkan selama ini terhadap Islam Jawa sebagai warisan Hindu bisa ditemukan dalam ajaran-ajaran skriptualis Hinduisme. Lihat Mark R. Woodward, Islam Jawa: Kesalehan Normatif versus Kebatinan, terj. Hairus Salim HS (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2004).

[9] Penganut Islam Wetu Telu tidak hanya di Bayan (Lombok Barat), tetapi juga di daerah lombok Tengah (Sengkol).Lihat Asnawi, Respon Kultural Masyarakat Sasak Terhadap Islam, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 11. Lihat Juga Fathurrahman Zakaria, Mozaik Budaya Orang Mataram (Mataram: Yayasan Sumurmas Al-Hamidy, 1998),hlm. 158.

[10] Erni Budiwanti, Islam..., hlm. 136. Juga John Ryan Bartholomew, Alif Lam Mim; Kearifan Masyarakat Sasak (Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 2001), hlm.98.

[11] Zaki Yamani Athar, Kearifan Lokal Dalam Ajaran Islam Wetu Telu di Lombok, Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 76.

[12] Fawaizul Umam dkk, Membangun Resistensi. Merawat Tradisi: Modal Sosial Komunitas Wetu Telu (Mataram: LKiM, 2007)

[13] Ahmad Zainul Hamdi, “Islam Lokal; Ruang Perjumpaan Universalitas dan Lokalitas” Ulumuna, Volume IX Edisi 15 Nomor 1 Januari-Juni 2005, hlm. 122-123.

[14] Amin Syukur, “Fiqh dalam Rentang Sejarah”, dalam Noor Ahmad dkk, Epistemologi Syara’; Mencari Format Baru Fiqh Indonesia (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2000), hlm. X.

[15] Karena secara sosiologis dan kultural, hukum Islam adalah hukum yang mengalir dan berurat berakar pada budaya masyarakat. Hal tersebut disebabkan karena fleksibelitas dan elastisitas yang dimiliki hukum Islam. Artinya, kendatipun hukum Islam tergolong hukum yang otonom –karena adanya otoritas Tuhan di dalamnya— akan tetapi dalam tataran implementasinya ia sangat aplicable dan acceptable dengan berbagai jenis budaya lokal. Karena itu, bisa dipahami bila dalam sejarahnya di sebagian daerah ia mampu menjadi kekuatan moral masyarakat (moral force of people) dalam berdialektika dengan realitas kehidupan. Baca Marzuki Wahid dan Rumadi, Fiqh Madzhab Negara (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2001), hlm. 81.

[16] Ratno Lukito, Pergumulan Antara Hukum Islam Dan Adat di Indonesia (Jakarta: INIS, 1998), hlm. 19. Kajian lebih lengkap tentang qaul qadim dan qaul al-jadid-nya Imam Syafi’i baca Jaih Mubarok, Modifikasi Hukum Islam; Studi Tentang Qawl Qadim dan Qawl Jadid (Jakarta: Raja Grafindo Persada, 2002). Lihat juga Hafizh A. Masro, “Perubahan Hukum Islam (Suatu Analisis Sosiologi Atas Pendirian Asy-Syafi’i)” dalam Al-Mawarid, Edisi Ketiga 1995,hlm. 12-22.

[17] Husein Muhammad, Spiritualitas Kemanusiaan Perspektif Islam Pesantren (Yogyakarta: Pustaka Rihlah, 2006), hlm.159.

[18] Untuk pemikiran Hasbi baca Yudian Wahyudi, Hasbi’s Theory of Ijtihad in the Context of Indonesian Fiqh (Yogyakarta: Nawesea, 2007). Tentang Hazairin baca Hazairin, Hendak kemana Hukum Islam (Jakarta: Tintamas, 1976). Juga Mahsun Fuad, Hukum Islam Indonesia (Yogyakarta: LkiS, 2005).

[19] Nurcholish Madjid, “Islam dan Budaya Lokal: Masalah Akulturasi Timbal Balik”, dalam Islam Doktrin dan Peradaban (Jakarta: Paramadina, 1992) hlm. 542-554.

http://klik-dunk.blogspot.com/2008/12/pergumulan-islam-dan-budaya-sasak.html